Your Genesys Blog Subscription has been confirmed!

Please add genesys@email.genesys.com to your safe sender list to ensure you receive the weekly blog notifications.

Subscribe to our free newsletter and get blog updates in your inbox

Don't Show This Again.

In just a few days, Genesys will launch three new inclusion groups for employees. As a member of an underrepresented minority group, the importance of this support network isn’t lost on me. When you often feel like the “only one” in your professional environment, having a network of others who experience office environments in similar ways is a kind of psychological safety net. Your shared experiences can inform each other and together you can motivate others in the organization for positive change.

Sharing professional experiences in inclusion groups is empowering for a variety of reasons, but part of the reason it particularly resonates with me is that my stories tend to be a little different than most. There are myriad reasons for this, but one stands out.

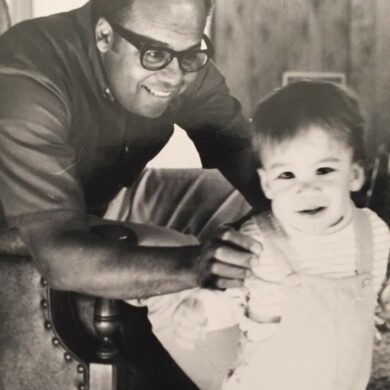

Me and my dad, ca 1968

I’m working undercover.

Growing up, I learned pretty quickly that I looked white to most people. I’m not. My late father was African American, and my mother is white. But my complexion gave me access to the private conversations of white people when they thought no Black person was around. I also learned early that revealing the nature of my identity could shut off the flow of information. If I didn’t reveal or emphasize my identity, I had access to whole worlds of conversation that my Black friends didn’t.

Staying silent wasn’t generally for me, but when I chose to, I could learn things. Things about how structural and institutional racism worked — and information about it that my father could never really know and that my mother was disinclined to teach me. The little things. When I entered the workforce, they stopped being so little.

During my final semester of college, I moved to San Francisco and took an internship with a large national bank. I was only going to be there for six months, but it was my first job in San Francisco, and I dove into the role. Dressing up every day, exploring new lunch spots and generally getting a lot more out of feeling young, empowered and employed during a recession than my wages could have ever afforded me alone.

The cast of characters that I worked with was mostly unremarkable and largely forgotten, save one. Gordon was an aging Englishman possessed with what was usually a dry British wit. One day Gordon returned from lunch looking shaken. I asked him what had happened, and he started telling me about an interaction he’d had with a “homeless Black guy.” These descriptors were the first cue.

“And then he went into his bad n****r routine to try and scare me…”

I don’t remember a single word of the rest of the conversation. My brain started sizzling inside my skull. I still have no recollection of how I responded, because I suppose that I really didn’t respond. I was caught flat footed. I walked away and seethed at my desk. Only many months later, when my boss took me out for drinks to celebrate my completion of the internship and the holidays, did I tell her what had happened. She was shocked. She promised to take some sort of action. I never found out if she did. But, I decided that I’d have to learn how to take action in the future. Because if I was sure of anything, I was suddenly and profoundly sure that things like this would happen again.

My second professional job would start a couple of months after the first ended. I was a copy editor — editing real estate appraisal reports for hotels, casinos and the like. It was a small company, but it was another “real job.” The recession had deepened, and I was ecstatic to find a gig that tracked to my skills. As a bonus I’d get a passive education in real-estate finance. Plus, my referral for the position came from another mixed person I trusted. I would be taking over her position. If it was cool for her, it would be cool for me.

My first few months were uneventful. Then came the office Christmas party. The managing director was a wonderful woman I genuinely trusted and liked. It was a fancy dinner with a lot of drinks. Her then boyfriend and future ex-husband Dennis decided to tell stories and jokes. He was showing off for his partner at the company Christmas dinner with 25 of her employees gathered around. I don’t remember the joke, but I do remember the punchline.

“Just like a n****r to bring a knife to a gunfight,” he concluded. And with that he laughed loudly.

“Actually, Dennis. That’s not what we do. We bring guns to gunfights. And some of us are right here in front of you. I’m mixed and I don’t appreciate that at all.”

All the air left the room.

A white colleague took up my cause. “Thanks for saying that DT. That’s not the way we should be talking right now. That wasn’t right, Dennis.” Later, privately, she would tell me that I was “courageous” and ask me if I remembered Dave Bing who played for the Detroit Pistons. She had grown up in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, with his son and the son had been a really great guy — and virtually the only Black student in her high school. I thanked her for speaking up. I silently thanked Dave Bing’s son wherever he was.

Outside, over a cigarette, Dennis apologized. I allowed it to be over. He talked about growing up in Gary, Indiana, one of the blackest cities in the country, his Black friends, his appreciation of the culture. I was numb. Not surprised or disappointed, numb. But I made a mental note to keep the conversation going, to help educate him when I could.

A few years later, I was recruited into the advertising industry. A close friend who believed in me as a writer thought I could be a solid copywriter. I decided to try a different approach this time. The friend who had recruited me knew that I was mixed and, by this time in my life, I had made an executive decision: Generally I would make my status and views public to the extent possible from very early on as a self-protection mechanism. If you knew who I was, you were probably less likely to be purposefully offensive in my presence. What I didn’t realize was the value that my blackness had in the world of advertising. I quickly learned.

Early in my tenure, I was offered a chance to work on an account that others were balking at, the online promotion for the Martin Lawrence film, “Big Momma’s House II.” My white colleagues were openly mocking the film and didn’t want to bother, I said I’d take it. I read the script and penned some ad units. But the coup de grace was creating a profile for “Big Momma” on BlackPlanet.com, then an afro-centric competitor to MySpace. All of the copy had to be approved by Martin Lawrence himself, allegedly. Needless to say, it would have been an impossible lift for a copywriter not fluent in African-American Vernacular English (AAVE). I wrote it; Martin approved it. The page’s popularity shocked my colleagues. More than 70,000 people interacted with the profile and left comments. Asking Big Momma questions. Wanting advice. Sharing stories. It was wild.

Everyone at the agency thought the whole thing was hilarious until the movie opened #1 at the box office. I went and saw it in the theater with pride. That theater was rocking. And there definitely wasn’t as much mockery at the next all-hands meeting when my tiny team got a standing ovation. But, make no mistake, some of it was still there.

But I had figured something out.

America loves Black culture. And America loves to use it to sell people products and services. Being the only Black copywriter in an ad agency is to live on a strange and mysterious island. You are trusted with the largest projects imaginable if there is a Black lead actor or a strong need for pitch-perfect slang. Working on another hugely prominent account for a global bank, I learned how to direct film. How? Because I was the only one who could coax the right lingo out of our young talent. Nobody else on set could imbue the lines with the right flavor. The work went on to win awards.

Building a Dynamic and Diverse Culture at Genesys

I’ve been in tech for more than a decade since leaving agency life. As with every professional job I’ve had, there is still an alarming lack of Black and Brown faces. I’m still here. I’m still working undercover. And I’m still waiting to see workplace diversity, equity and inclusion arrive in full. That’s why it is so encouraging to be actively working with my employer to build a company culture that’s dynamic in its approach to diversity, equity and inclusion.

Inclusion groups are a great start. They build bridges. They attract true allies — people who aren’t afraid to learn how other people feel, to learn how mechanisms of institutional discrimination work and what we can do to limit their effectiveness or root them out. I am overjoyed to be a part of the team that’s helping launch them at Genesys. In the faces of the younger employees coming together in a grassroots way to launch them, I see reflections of my younger self, supported in ways that I wasn’t.

As I help moderate the conversation that launches inclusion groups at Genesys I’ll be doing so with an eye toward the windshield rather than the rear-view mirror. The road ahead feels genuinely hopeful. It feels as if the majority of my professional peers are ready to have real conversations about prejudice and discrimination in the workplace. It feels like people are really ready to see things change. And, while I might still be working undercover in the eyes of some, feeling included in a way that allows me to feel more comfortable being my authentic self as a professional is empowering.

I might still be working undercover occasionally, but it feels great to think that future generations might not ever feel they need to.

Subscribe to our free newsletter and get blog updates in your inbox.